Part 1: The World Runs on Differential Equations

The world, quite literally, runs on differential equations. From the airflow over an aircraft wing to the design and manufacture of a computer chip, almost every engineered system is governed by equations describing how things change. Physicists, mathematicians, and the occasional adventurous engineer, have long preoccupied themselves with understanding such systems and finding efficient ways to predict their behaviour. Ordinary, algebraic, partial, or stochastic differential equations are the often-invisible engines of industrial R&D. They underpin the models that describe how materials behave, how electrons flow in circuits, how heat diffuses through complex systems, and even how good your Wi-Fi connection will be.

Recently, large language models have captured the cultural AI spotlight (and more than a few supercomputers). But the real numerical heavy lifting still happens elsewhere. The unsung heroes are the solvers of Navier–Stokes, Schrödinger, Maxwell, Kirchhoff, Newton, and other equations that capture the fabric of reality. They break down complex problems and help us understand how to (and often how not to) build the technologies that power modern life.

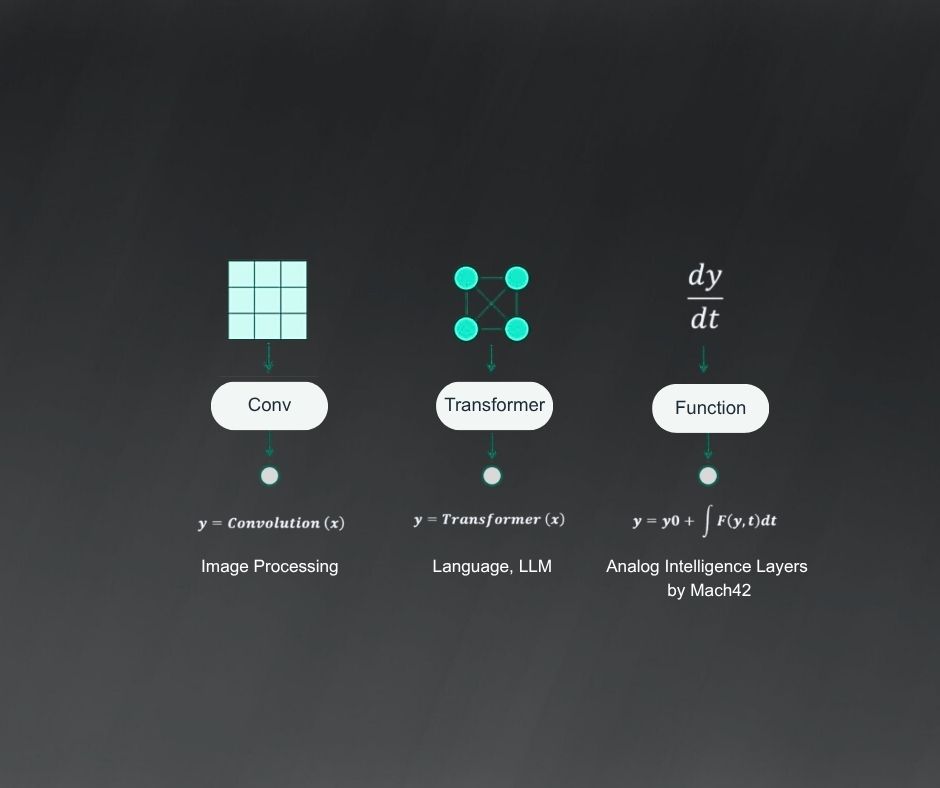

Now, AI is starting to speak this language too. A new generation of physics-informed AI models are beginning to learn the very differential equations that govern complex systems, rather than just inferring outcomes from data. By seeking to capture the underlying dynamics directly, these methods can model behaviour across a wide range of evolving physical systems with unprecedented fidelity, from analogue electronic circuits to non-linear plasmas. Woven into simulation pipelines, they offer the promise to surrogate expensive solvers, accelerate parameter sweeps, and enable robust multi-physics co-simulation. Instead of replacing physicists and engineers, this technology augments them: working alongside numerical solvers and respecting the laws of physics, AI can help to uncover patterns across vast parameter spaces and optimise systems too intricate to be simulated end-to-end by conventional means.

The shift may also be architectural. Just as deep learning swapped the CPU for the GPU, so too may numerical simulation. Physics-informed neural networks, operator learning, and hybrid AI-solver frameworks are beginning to migrate centuries of calculus onto modern accelerators. This marriage of physics and data could turn traditional simulations into adaptive, continuously learning systems that model the world in real time.

So yes, chatbots are clever. They help write code and design beautiful websites. But the equations that predict the weather, design chips, or harness fusion—that’s where AI’s next quiet revolution is brewing. After all, if the world runs on differential equations, what better task for the next generation of AI than to learn to solve them.

Coming up: Part 2 about Pioneering New Modelling by our Chief Technology Officer, Brett Larder.